Losing Value. By Adam M. Grossman.

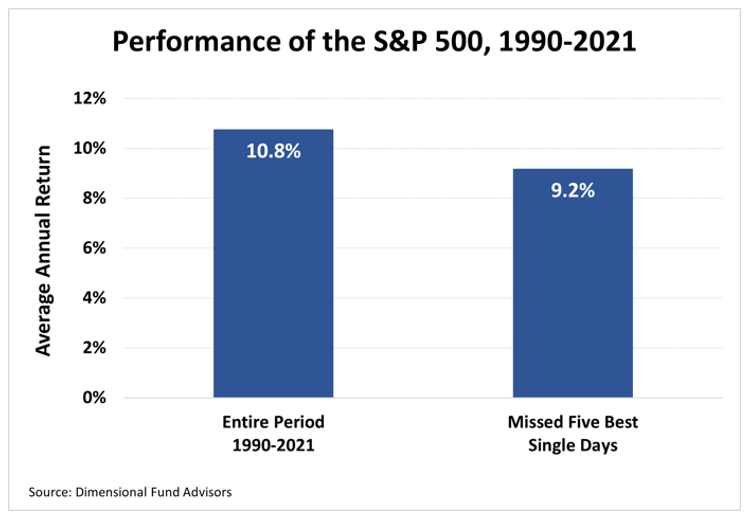

Perhaps you’ve seen charts like the one below, which comes from Dimensional Fund Advisors. The message: Investors who try to time the market in search of better returns often end up damaging their results. To many investors, this seems intuitive, because trading isn’t easy.

But to others, market timing appears to make a lot of sense. For instance, for years, Yale University professor Robert Shiller has been maintaining a measure of market valuation known as the cyclically adjusted price-earnings (CAPE) ratio. It’s a way of measuring how expensive the market is, and it has an intuitive appeal of its own.

In 2000, for example, the dot-com bubble was clearly visible on a chart of the CAPE ratio. Sure enough, the market experienced a steep decline from that peak, falling nearly 60%. Similar patterns are visible around the market tops in 1929 and in the late 1960s.

It’s data like this that makes many folks believe in market timing. For them, it’s just plain common sense to sell stocks when they’re overpriced and to buy them when they’re underpriced. For those who believe in market timing, it would appear borderline reckless to take a buy-and-hold approach, given how clear a guide the CAPE ratio appears to be.

Who’s right in this debate? In a recent study, Derek Horstmeyer, a professor at George Mason University, looked at this question. Together with colleagues, he used 100 years of market data to compare the returns of two hypothetical portfolios: a static 50% stock-50% bond portfolio and an actively traded portfolio that adjusted its holdings in response to market valuation.

The actively traded portfolio used what Horstmeyer called a “20-12” trading rule. During periods when the CAPE ratio was between 12 and 20—meaning the market was neither particularly expensive nor particularly cheap—the active portfolio held the same 50% stock-50% bond allocation as the buy-and-hold portfolio. But when the market got expensive, with the CAPE over 20, the active portfolio shifted to a more defensive stance, with just 30% in stocks and 70% in bonds. Meanwhile, when the market fell into bargain territory, with the CAPE under 12, the active portfolio became more aggressive, shifting to a 70% stock-30% bond allocation.

What did Horstmeyer’s team find? Historically, the 20-12 trading strategy would have worked well, delivering outperformance of about 0.4 percentage point a year. That’s not enormous. But compounded over many years, it would have been meaningful. There’s one problem, though: Horstmeyer found that this outperformance was short-lived. Initially, the outperformance was there. But in 1950, the results reversed. Between 1950 and 2000, the buy-and-hold approach outperformed the active strategy by about 0.8 percentage point a year. And since 2000, the buy-and-hold strategy’s advantage widened further, to 1.9 percentage points a year.

These results make sense. Over time, and especially since the advent of the internet, it’s become much easier for everyday investors to access market information. This has made it much harder for professional investors to beat the market by having access to more information. There’s a famous story, for example, about Benjamin Graham. He’s regarded as the father of modern investment analysis and was an early hedge fund manager.

In 1926, he was studying the railroad industry, when he got an idea. The next day, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to get a look at industry data that was available only on paper, in the office of the Interstate Commerce Commission. Sure enough, Graham found what he was looking for, and that led to a 50% gain on the stock he identified. This opportunity, though, was one that was only obvious to someone willing and able to sift through files in a government office. Today, anyone with an internet connection could do the same thing—and that, I think, helps explain Horstmeyer’s findings.

Things began to change even before the internet. In 1976, near the end of his life, Graham made these comments in an interview: “I am no longer an advocate of elaborate techniques of security analysis in order to find superior value opportunities. This was a rewarding activity, say, 40 years ago…. I doubt whether such extensive efforts will generate sufficiently superior selections to justify their costs.”

The lesson for investors: There’s no question that market timing seems intuitive. It feels like the right thing to do. So, why does the data so clearly point in the other direction? In addition to greater data availability, I see two other factors.

First, the market isn’t always rational. Often, when valuations are high, they end up going higher still. Look at the CAPE ratio during the 1990s to see a clear example. A rational investor might have concluded that the market was overpriced as early as 1993, when the CAPE crossed 20. But then it kept going. By 1995, it had topped 25 and, in the end, it went as high as 44. To be sure, an investor who had sold back in 1993 would have avoided the meltdown that occurred in 2000, but he also would have missed out on seven years of gains, which would have far outweighed those later losses.

The second reason a valuation-based approach to trading doesn’t work in practice is that the market is unpredictable, making it impossible to know when it might move higher. We saw this as recently as 2020. In the spring, the economy had largely come to a stop, the market had dropped more than 30% and most people had no idea how long the crisis would last. But on March 23, the Federal Reserve stepped in to contain the damage, and the market immediately turned higher. The market gained 9% the next day and 14% by the end of that week. A month later, the S&P 500 had gained 28%. By year-end, it was up 68% from its low point.

What Horstmeyer’s study makes clear, in other words, is that valuation ratios are just one factor in determining the direction of the market. World events are at least as important, and there’s no chart that can tell us what might be around the corner. A ceasefire in Ukraine, for example, would likely spark a market rally, but no one knows when or if something like that might happen. The bottom line: Difficult as it might be sometimes, investors’ best bet is to choose an asset allocation—and then to stick with it.